Our initial findings raise three critical and closely-interrelated questions which the project aims to address: (1) Did human ingenuity alone allow the Byzantines to flourish in the marginal environment of the Negev? (2) Were the Byzantines aided by climatic improvements such as increased regional water budgets? And, finally (3) Why did this highly successful system eventually fail?

March 2015

Pilot excavations have unearthed highly promising discoveries, demonstrating the great and as yet nearly untapped potential of a bio-archaeologically oriented project in the Negev. Whereas previous expeditions to Shivta and Halutza in the 1930s and 1970s surmised that nearby mounds formed due to removal of wind-blown sands from city streets, our initial explorations reveal a very different story: The mounds are in fact composed of dense accumulations of household and industrial trash removed from houses. Through high-resolution excavation in conjunction with intensive sieving and flotation operations applied to mound sediments we retrieved both artifacts and biological remains in high concentrations. Similar discoveries were made while exposing an ancient structure located outside the settlement of Khirbet Sa’adon: Overlying the floor of the structure dozens of nearly-complete pigeon skeletons and remains of pigeon manure were uncovered. It is likely that Byzantine farmers used such installations to enhance the productivity of nutrient-poor soils in the Negev.

December 2015

Excavations at the site of Shivta now reveal further tantalizing evidence for complex historical trajectories on both sides of the 640 AD temporal divide between the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods. On the one hand, sealed doorways of several Byzantine structures testify to organized abandonment of particular sections of the local populace (Tepper et al. 2015, See below), and on the other, the finding of a major inscription from one of the Byzantine churches in secondary use suggests that the Christian population of the settlement was largely replaced or converted during the Islamic period (Dec. 2015 Ha’aretz Report). These findings together with ongoing analyses of associated assemblages of bio-archaeological materials and chronometric determinations will make a pivotal contribution to clarifying the sequence of population transitions in the dynamic history of Shivtaand their underlying causes.

Grape seeds (Vitis vinifera; Left) and jaw of parrot fish (Scarus collana; Right) recovered from an ancient landfill at Halutza, Late Byzantine period in the 5th-6th centuries AD. The presence of these remains in everyday household trash suggests large-scale vine cultivation and long-distance trade relations extending at least to the Red Sea.

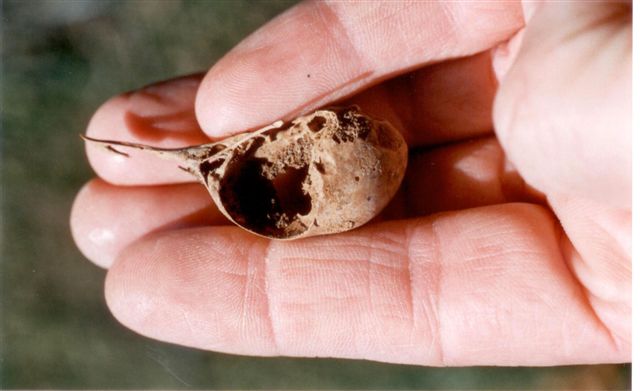

Intact pigeon skull (Left) and manure (Right) retrieved from an ancient pigeon-raising installation near the site of Khirbet Sa’adon.

Pottery analysis conducted by Dr. Tali Erickson-Gini onsite (Left) and at our field laboratory (Right) during the Halutza campaign.

Six examples of sealed door openings at Shivta, including doors that are completely barricaded (1) and others that are sealed using finely dressed masonry (2–5) or small unmodified stones (6). Taken from Tepper et al. 2015: Figure 3.